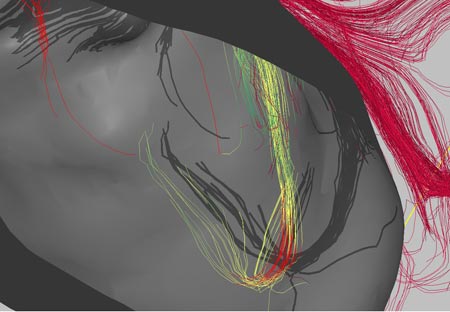

Technology Review has an interesting article about “new” 3D brain imaging software being developed at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, PA (I put “new” in quotation marks because there are other similar programs out there; they might not be as polished but some are even open source). Their software fuses MRI, fMRI, and DTI together to create a fairly comprehensive view of the brain: “The fusion of these different images produces a 3-D display that surgeons can manipulate: they can navigate through the images at different orientations, virtually slice the brain in different sections, and zoom in on specific sections.”

The software looks like it is aimed more at neurosurgeons than researchers (i.e., it probably isn’t free like a lot of MRI image processing software). It does produce amazing images (view the images here) and looks like it could be a very useful tool for at least a qualitative approach to brain imaging.

The software is focused a lot on DTI (diffusion tensor imaging) and how the white matter fibers in the brain interact with lesions or tumors. I think that one researcher’s word of caution is important:

“Bruce Fischl, an assistant in neuroscience at Massachusetts General Hospital, says that the idea is ‘interesting’ but cautions that there are a number of levels of ambiguity when talking about connectivity in imaging. ‘Just because you live next to the Mass Pike doesn’t mean that there is an exit,’ he says.”

In other words, don’t get too caught up in the fact that fibers are right by a tumor, they may not really have anything to do with the part of the brain the tumor is most affecting.

In any case, I think that the idea behind this software is amazing. The graphics renderings are impressive (but they are just the pretty pictures – the rendering details may be beneficial in clinical surgery settings but they are not particularly useful in research situations, other than producing nice pictures to go in your publication). This software is very similar to something that I envisioned using a few years ago and I’m glad to see it being developed.

Image credit: Song Lai, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital (borrowed via technologyreview.com)

The positron emission tomography (PET) scan measures blood flow in the brain. This is accomplished by injecting a person or animal with a radioactive isotope (i.e. an unstable atom, usually a variation of oxygen that has a short-half life); this isotope will quickly decay. Founded on the assumption that blood flow will increase in areas of the brain that are in heavy use (such as when a person is viewing an object or reading words or some other cognitive-intensive function), a fair portion of the injected isotopes will end up in the active part of the brain. As the isotopes decay, a positron (a small particle with the exact opposite charge as an electron) is released. This positron will collide with an electron and they will annihilate each other, sending two gamma ray particles in exactly opposite directions. These gamma rays are picked up by the PET scanner, which then determines where they came from in the brain. Since blood should concentrate where the brain is activated, there should be higher levels of isotopes there and this will show up on the scanner in the form of increased levels of gamma rays. The test is usually run twice (once as the control condition and once as the experimental). The difference between the two conditions is measured and any difference should show what area(s) of the brain was (or were) activated.

The positron emission tomography (PET) scan measures blood flow in the brain. This is accomplished by injecting a person or animal with a radioactive isotope (i.e. an unstable atom, usually a variation of oxygen that has a short-half life); this isotope will quickly decay. Founded on the assumption that blood flow will increase in areas of the brain that are in heavy use (such as when a person is viewing an object or reading words or some other cognitive-intensive function), a fair portion of the injected isotopes will end up in the active part of the brain. As the isotopes decay, a positron (a small particle with the exact opposite charge as an electron) is released. This positron will collide with an electron and they will annihilate each other, sending two gamma ray particles in exactly opposite directions. These gamma rays are picked up by the PET scanner, which then determines where they came from in the brain. Since blood should concentrate where the brain is activated, there should be higher levels of isotopes there and this will show up on the scanner in the form of increased levels of gamma rays. The test is usually run twice (once as the control condition and once as the experimental). The difference between the two conditions is measured and any difference should show what area(s) of the brain was (or were) activated.